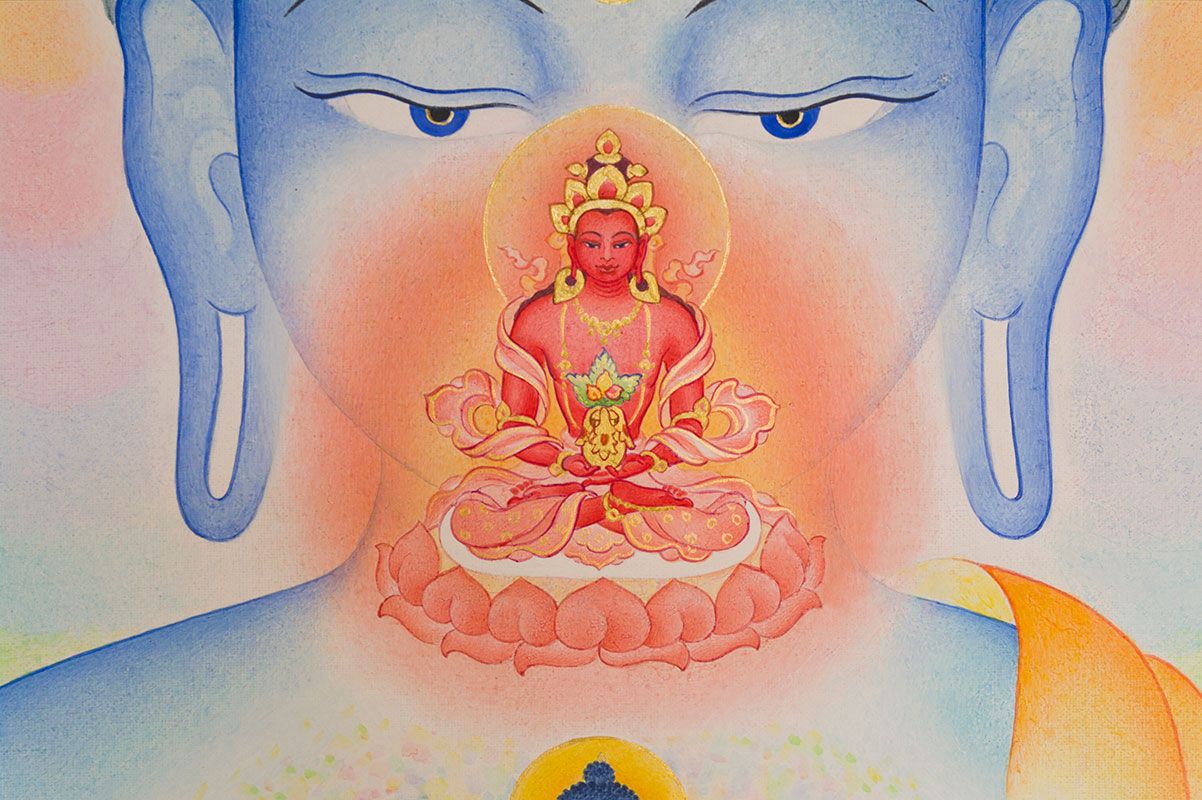

Emptiness is the central insight of Buddhism, and what makes it unique among religions. According to Buddhism, neither we, nor other beings, nor any phenomenon in the universe, has a permanent, separate, and independent core, soul, or identity. Another way to look at it is interdependence: all relative phenomena are purely the product of external causes.

The word “emptiness” is best known for its central place in the Heart Sutra of the Mahayana tradition: “Form is emptiness; emptiness is form,” a phrase that is repeated also for the other four aggregates that construct our idea of self—feeling, perception, formations, and consciousness. The sutra goes on to say that “emptiness is the nature of all things,” thus expanding the psychological insight that a person is empty of self to the comprehensive metaphysical insight that all phenomena are empty of self-nature.

The 2nd-century philosopher Nagarjuna explains this with greater precision in his treatises by drawing out the implications of the teaching on impermanence and dependent origination. All things are in the perpetual process of arising and passing away, ever “becoming” and thus never actually “being.” Conditioned by multiple interdependent causes, all things are “empty” of any sort of independent or intrinsic nature and thus defy conceptualization.

To understand emptiness we should start with understanding impermanence.

Self, action, object; friend, enemy, stranger; all the sense objects—desirable, undesirable, indifferent—all these are transitory in nature, changing within each second due to causes and conditions. These things can cease at any time. This also applies to our own body, our possessions, our friends and relatives.

Therefore, there is no reason to have the dissatisfied minds of desire, anger and ignorance, or the wrong conception that these things are permanent, that they do not change but last forever. There is no benefit in believing this, since it is not the nature of these things. It brings only problems, confusion. All these things change and cease. When that happens, there is a problem in the mind, a problem in the life.

Empty of What?

Emptiness, or selflessness, can only be understood if we first identify that of which phenomena are empty. Without understanding what is negated, you cannot understand its absence, emptiness.

You might think that emptiness means nothingness, but it does not. All the objects, everything is empty of inherent existence.

A consciousness that conceives of inherent existence does not have a valid foundation. A wise consciousness, grounded in reality, understands that living beings and other phenomena—minds, bodies, buildings, and so forth—do not inherently exist. This is the wisdom of emptiness. Understanding reality exactly opposite to the misconception of inherent existence, wisdom gradually overcomes ignorance.

Do Objects Exist?

Phenomena certainly do exist not in the way we think they do; the question is how? They do not exist in their own right, but only have an existence dependent upon many factors, including a consciousness that conceptualizes them.

Once they exist but do not exist on their own, they necessarily exist in dependence. However, when phenomena appear to us, they do not at all appear as if they exist this way. Rather, they seem to be established in their own right, from the object’s side, without depending upon a conceptualizing consciousness.

Buddha said many times that because all phenomena are dependently arisen, they are relative—their existence depends on other causes and conditions and depends on their own parts. A wooden table, for instance, does not exist independently; rather, it depends on a great many causes such as a tree, the carpenter who makes it, and so forth; it also depends upon its own parts. If a wooden table or any phenomenon really were not dependent—if it were established in its own right—then when you analyze it, its existence in its own right should become more obvious, but it does not.

Because the true nature of objects is emptiness, they are therefore incapable of performing functions such as causing pleasure or pain, or helping or harming, is the worst sort of misunderstanding, a nihilistic view.

There are some traditional contemplations you can do to investigate this. Choose any object, say a chair, and see if you can find the one essential thing that makes it a chair. You can do the same thing with concepts themselves: is there an independent thing called “good,” or does its existence depend on “bad”? Another view of emptiness is that what things are empty of is our projections on them, from “chair” and “me” all the way up to “existence” and “nonexistence.” In the end, of course, emptiness has to go beyond intellectual understanding to direct experience.

Further Reading:

Nagarjuna – click here